The brightest stars of early Danish film

Julie K. Allen, Professor, Brigham Young University, Utah | 12 December 2019

In the silent era, Denmark produced several of its most successful and prolific film stars, most notably, in the 1910s, Asta Nielsen (1881-1972), Olaf Fønss (1882-1949), Clara Wieth (Pontoppidan) (1883-1975), Valdemar Psilander (1884-1917), and, in the 1920s, Carl Schenstrøm (1881-1942) and Harald Madsen (1890-1949). Although Asta Nielsen’s name is the most internationally recognized today, all of these actors were among the most famous and beloved screen personalities of their time, at home and as far afield as Australia, Brazil, and Russia. Between them, they made nearly four hundred films in Denmark, Sweden, England, and Germany, reaching audiences around the globe and earning Danish film international prestige.

Taking the leap from theater to film

These stars’ remarkable success was due in part to being in the right place at the right time, with the necessary skills to take advantage of Denmark’s early prominence in the film industry. Born in successive years in the early 1880s (with Madsen bringing up the rear in 1890), they all got their start in the early 1900s in live theater (or the circus, in Madsen’s case), which offered a way out of poverty, an alternative to menial labor, and freedom from bourgeois conventionality and were in their mid-20s when the Danish film industry took off. Despite the low cultural status of film at the time, growing domestic and international demand rapidly made the Danish film industry lucrative. Film length and budgets increased quickly over the first decade of the 1900s, from one-minute long films costing maximum 100 kroner each to make to hour-long films costing hundreds of thousands of kroner. Although Copenhagen theater directors tried to forbid their actors from making films, the higher wages were a compelling draw, particularly once multi-reel fiction films offered stage actors a chance to display their acting skills to advantage on screen.

Although the four actors who shaped Danish film in the 1910s were largely motivated by financial considerations to venture into filmmaking – Nielsen, Wieth, and Psilander in 1910, Fønss in 1912, each of them helped elevate Danish social dramas to a critically acclaimed art form, earning significant personal celebrity along the way. As the global film industry redefined itself after World War I, Schenstrøm and Madsen became famous as a comic team (under the names Fy & Bi, Pat & Patachon, Long & Short, Ole & Axel, etc., depending on the country), when war-weary audiences were eager for a reason to laugh.

The making of Danish movie stars: Clara Wieth and Valdemar Psilander

Wieth, Psilander, Nielsen, and Fønss each got their start in film independent of Nordisk, but they all ultimately made their way to Nordisk, if only briefly in Nielsen’s case. Wieth led out, making her first film with Regia Kunstfilms, the 10-minute short Elskovsleg (Flirtation), in May 1910, and then co-starring with Psilander in Dorian Grays Portræt (The Portrait of Dorian Gray) later that same year. Wieth’s and Psilander’s performances in this otherwise mediocre film brought them to Olsen’s attention; he promptly engaged both of them for leading roles in larger-budget productions. For her first Nordisk film, Wieth played the unfortunate female lead in Den hvide Slavehandels sidste Offer (In the Hands of Imposters,1911), the sequel to Nordisk’s first blockbuster erotic melodrama, Den hvide Slavehandel (The White Slave Trade, 1910), which it had plagiarized from the Aarhus-based company Fotorama’s successful film released earlier that year. Wieth’s salary for this film was 300 kroner, much more than the 5 kroner a day earned by an extra on the film, but still a pittance compared to Olsen’s profit, which Wieth estimated to be at least 100,000 kroner. Still, the film established Wieth as a bankable star, which Olsen also appreciated. One day not long after the film’s premiere, Olsen visited Wieth at home and gave her a 100 kroner note, with the remark, “Here’s a gratuity for you, Mrs. Wieth.” Wieth reflected later, “the most important part of it for me personally was that, from then on, a film with Clara Wieth could sell, which at that time meant in the whole world, even before it had been made. Yes, I had found a sweet spot for myself out there in Valby.” 1 Droves of letters and gifts from fans poured in; Wieth later recalled, “Oh, what I didn’t get in the way of exciting letters and billet-doux with praise for my blondness and Nordic expressiveness.” 2

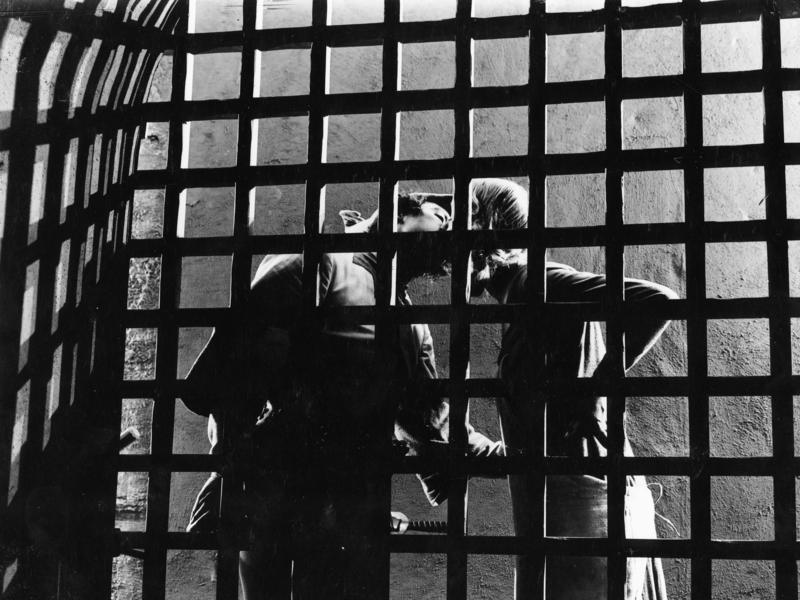

Psilander’s first film with Nordisk, playing opposite Wieth, was Ved Fængslets Port (Temptations of a Great City, 1911), for which he demanded the princely wage of fifty kroner a day, twice what he had earned for The Portrait of Dorian Gray. Fortunately for Nordisk, the gamble paid off. Temptations of a Great City proved to be the company’s greatest success since Løvejagten (The Lion Hunt) in 1908, selling 246 prints, more than twice as many as The White Slave Trade. The story of a young man living beyond his means and struggling with the temptation to defraud his long-suffering mother resonated with audiences around the globe. Within five months of its Danish premiere, it was being screened in Australia, where it remained in circulation for three full years—showing first in metropolitan cinemas in Sydney, Melbourne, Launceston, Adelaide, and Brisbane, then in provincial theaters across the country, and finally moving through rural areas with a traveling cinema show. Wieth and Psilander played opposite each other in several of her nearly fifty silent films, co-starring in such films as Mormonens Offer (Victim of the Mormons, 1911), another reworking of the white slavery motif with an American angle, and Holger-Madsen’s 1916 light-hearted drama about star-crossed lovers, Manden uden fremtid (The Man Without a Future, 1916). In the latter film, screenwriter Harriet Bloch’s script allocates almost 75% of the film’s running time to Psilander’s character, the dashing cowboy-turned-aristocrat Percy Fancourt, relegating Wieth to a small but endearing supporting role.

Wieth also co-starred in several films with her first husband, the actor Carlo Wieth. An excellent example of their work together is Ekspeditricen (In the Prime of Life / The Girl Behind the Counter), directed by August Blom in 1911, a social drama about a romance doomed by class differences and an ill-timed pregnancy. While Carlo Wieth enjoyed significantly more screen time than Clara in that film, she stole the show when they appeared together in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1921 film Blade fra Satans Bog (Leaves from Satan’s Book) as an anti-Communist Finnish couple.

The memorable close-ups in which her character Siri chooses to stab herself in the heart rather than commit treason conclusively demonstrated Wieth’s tremendous expressive range. The next year, she shone both as a nun in Benjamin Christensen’s budget-busting, horror-tinged pseudo-documentary Häxan (Witchcraft through the Ages, 1922) and as the imperious, ruthless fairy-tale princess of Illyria in Dreyer’s Der var engang (Once upon a time, 1922), an adaptation of Holger Drachmann’s 1884 play of the same name. From the mid-1920s onward, however, Wieth devoted herself primarily to live theater.

Although he was known as “Verdens Valdemar” (“the world’s Valdemar”) for his international popularity, Psilander made all of his nearly ninety films in Denmark, most of them with Nordisk. After the runaway success of Temptations of a Great City, Psilander became the leading actor at Nordisk, with his workload, his wages, and his fame rapidly increasing. By 1912, he was reportedly earning 10,000 kroner per film, an astronomical compensation for the time, but one justified by his immense popularity. A decade before the Italian American actor Rudolph Valentino became the world’s heartthrob, Psilander’s dark good looks earned him adoring fan mail from around the world. Danish journalist Helge Wamberg attributed Psilander’s success to his “good body, a handsome face, and an attractive smile,” none of which Wamberg regarded as particularly Danish. Instead, Wamberg said of Psilander, “His temperament did not belong to our climes. There was something foreign, dominating in his being, which is not Danish. ... He was born to impress and to charm. And it was with the help of these valuable treasures that he became the most talked-about film star in the world, the irresistible and unconquerable.” 3 Of the more than seven dozen films he made between 1911 and his sudden death in 1917, Psilander’s performances in an earnest pastor among criminals in Holger-Madsen’s Evangeliemandens liv (The Candle and the Moth) in 1915 and as a disillusioned circus clown determined to avenge his wife’s betrayal in A.W. Sandberg’s Klovnen (The Clown, released in 1917) stand out for their divergence from the stereotype of the elegant society gentleman that he was so often required to embody, as for example in the two films he made with Asta Nielsen in 1911, Den sorte Drøm (The Black Dream/ The Circus Girl) and Balletdanserinden (The Ballet Dancer).

The road to success through Germany: Asta Nielsen and Olaf Fønss

Nielsen made her first film, Afgrunden (The Abyss / The Woman Always Pays) at around the same time as Wieth and Psilander’s Portrait of Dorian Gray, but her path to global stardom was even more meteoric than theirs as she became the first international movie star brand. Frustration with a lack of opportunities on the stage in Copenhagen, a problem that Olaf Fønss later attributed to Nielsen’s “foreign appearance and her bold manner,” 4 led Nielsen and Gad to make their first film together in order “to show the theater directors in Copenhagen what we two were capable of." 5 They little dreamed how much this film would change not only their own lives but the global cinema industry as well. Unable to interest Nordisk in making or distributing their project, they secured 8000 kroner to make the film from Hjalmar Davidsen, a friend of Gad’s who owned the Kosmorama movie theater on Østergade in Copenhagen. The film, with its melodramatic love triangle between a piano teacher, a pastor’s son, and a circus cowboy, and Nielsen’s provocative “gaucho” dance, proved to be a runaway success in Denmark and abroad. Even when the German distributor Ludwig Gottschalk bragged about earning 800,000 German marks on screening the film in Düsseldorf alone, Olsen defended his decision to his London office with the explanation, “We don’t find her [Nielsen] particularly good, but that is a matter of taste, after all." 6

Fortunately for audiences, neither Fotorama in Aarhus nor Deutsche Bioscop in Berlin shared Olsen’s opinion of Nielsen’s abilities. The former company hired Nielsen to make The Black Dream, playing a circus rider opposite Psilander’s impoverished nobleman, while the latter engaged her for a series of films to be made in Berlin. Since Fotorama had no atelier, the technical quality of The Black Dream was not as high as films made by Nordisk in the same period, but both Nielsen’s erotic appeal, in her tight black leotard, and her masterful acting came through clearly. Film historian Marguerite Engberg argues that, of all of Nielsen’s surviving films, The Black Dream is the one in which Nielsen’s “unique beauty comes into its own,” not least because it offers the first close-up of Nielsen’s face. 7

Nordisk did eventually hire Nielsen in late 1911 to make The Ballet Dancer, another love triangle film directed by August Blom, for which she earned 5,000 kroner, but it was too little, too late to keep her in Denmark. 8 Immediately after making The Ballet Dancer, Nielsen accepted an offer of 80,000 German marks a year to film exclusively in Berlin with Deutsche Bioscop. Her arrival in Germany coincided with the beginning of the monopoly film distribution system, which required stars with enough prestige to sell entire series of films sight unseen, often before they had even been made.

As the first representative of this star system, Nielsen’s films, her image, and her name were soon exported to the entire world, associated with all manner of branded wares. With the exception of Mod Lyset (Toward the Light, 1918), which featured Carl Schenstrøm as the devil trying to dissuade Nielsen’s bereaved character from becoming an evangelist, Nielsen made all the rest of her seventy-plus fiction films in Germany, ending with a single sound film in 1932.

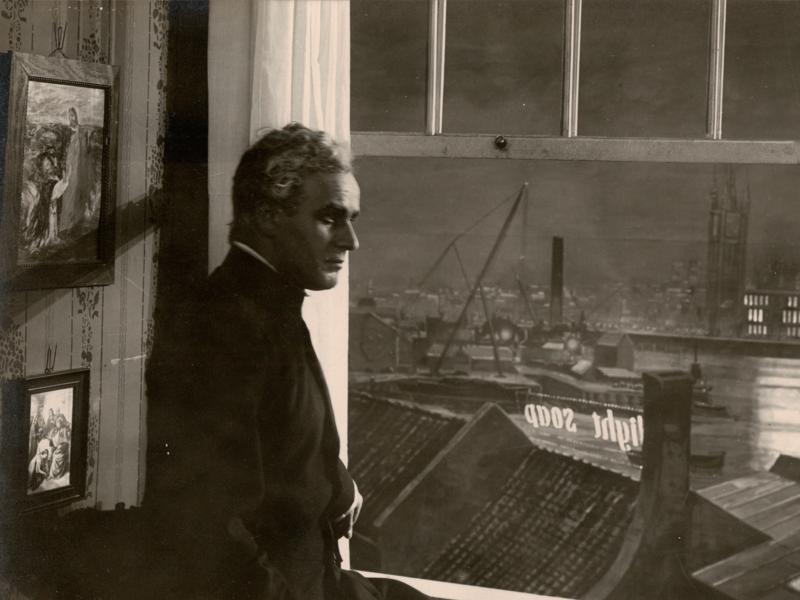

Olaf Fønss was the last of the quartet of Danish stars to begin making films, with the company Scandinavian-Russian Handelshus in 1912, but he also achieved international fame very quickly, particularly after his star turn as Dr. Friedrich von Kammacher in August Blom’s film Atlantis from Nordisk in 1913. Based on German author Gerhard Hauptmann’s novel about the sinking of a trans-Atlantic liner, Atlantis cost an estimated 300,000 kroner, the most expensive film made in Denmark to that point. In an attempt to stay true to the novel, the film is more concerned with Fønss’ character’s mental state than with the shipwreck itself, making Fønss the focal point of viewers’ attention. Atlantis was not a great success in Denmark, but was tremendously popular in Germany, which launched Fønss’ global reputation and led to all manner of offers—some economic, like the one from his co-star, the Viennese dancer Ida Orlov, to perform on the German stage for 5000 Reichsmarks a month, and others erotic, including one from a young Viennese noblewoman asking for his “favor” for a week in order to conceive a child with the hero of Atlantis; if the child was a girl, she promised to name it Atlanta. 9 Fønss went on to make another five dozen films in the silent era, primarily in Denmark at Nordisk and then with the film company that Psilander had founded shortly before his death—including Lægen (The Plague, 1918), opposite Clara Wieth—, as well as an acclaimed series of Homunculus films in 1916-17 and the two-part 1921 Joe May epic Mysteries of India, based on a screenplay by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou, in Germany.

A shift to comedy: Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen

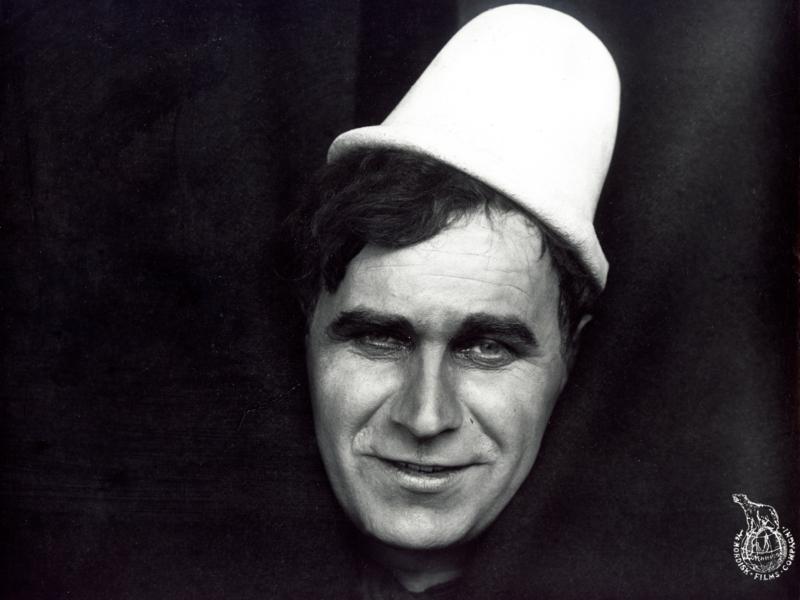

The Danish film industry’s preoccupation with social dramas waned after World War I, accelerated by Nordisk’s financial difficulties after losing its German cinema network, making room for the rise of Denmark’s most famous pair of comedians, Carl Schenstrøm and Harald Madsen. Director Lau Lauritzen had made his name in the six years he worked at Nordisk with such comic short films as Don Juans Overmand (Don Juan’s Boss, 1916) and Min Svigerinde fra Amerika (My Sister-in-Law from America, 1917), which poked fun at Danish social mores and self-righteousness, before moving to the Swedish film company Palladium in 1920. His repeated attempts to find the right combination of comic actors to play off each other succeeded resoundingly with the pairing of the tall, lanky Schenstrøm with the short, rotund Madsen in 1922, whose first feature film together Film, Flirt og Forlovelse (Film, Flirtation, and Engagement) established the characters that would enable them to take the world by storm: Schenstrøm’s somewhat melancholy, good-hearted but mischievous Fyrtårn (lighthouse) and Madsen’s naïve, cheerful Bivognen (sidecar), as they were known in Danish, though generally shortened to Fy and Bi. Marguerite Engberg explains that the first scene in Film, Flirtation and Engagement is already typical of their interactions, with Fy “the initiative-taker, the clever one, Bivognen equipped with youthful daring, coupled with naïveté or stupidity.” 10

As their popularity spread around the world, most widely under their German names Pat and Patachon, Schenstrøm and Madsen made several successful films in Berlin and England, but they always came back to Denmark. Their 1927 film Vester Vov-Vov (People of the North Sea / At the North Sea) is an excellent example of their later silent films, a love story combined with an action film, in which Fy & Bi manage to resolve a thorny local love triangle while on a pleasure fishing holiday on the Danish North Sea coast. The Danish daily, Horsens Folkeblad, rejoiced at their return to Danish shores, exclaiming that “laughter billows around them, whether they’re being tossed around on a breakneck carousel ride, directed by a dolphin out in the midst of ocean waves, or performing a wild and violent Charleston in a pub." 11 Despite Madsen’s increasingly frail health, they managed the transition to sound film better than most silent stars, even remaking some of their most popular films, such as their 1922 hit Han, Hun, og Hamlet (He, She, and Hamlet), in sound versions in the early 1930s.

Notes

1. Clara Wieth Pontoppidan, Eet liv—mange liv (Copenhagen: Steen Hasselbalchs Forlag, 1968), 214.

2. Pontoppidan, Eet liv, 210.

3. Helge Wamberg, Valdemar Psilander (Copenhagen: Nyt Nordisk Forlag, 1917), 6.

4. Olaf Fønss, Danske skuespillerinder (Copenhagen: Nutids Forlag, 1930), 117.

5. Asta Nielsen, Den tiende muse (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1966), 102.

6. Marguerite Engberg, Dansk Stumfilm Vol. 1. (Copenhagen: Rhodos, 1977), 260.

7. Engberg, Asta Nielsen, 230

8. Poul Malmkjær, Asta: Mennesket, myten og filmstjernen (Copenhagen: P. Haase & Søn 2000), 89.

9. Arnold Hending, Olaf Fønss (Copenhagen: Urania, 1943), 87.

10. Marguerite Engberg, Fy & Bi (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1980), 27.

11. Engberg, Fy & Bi, 74.

Julie K. Allen, Professor, Brigham Young University, Utah | 12 December 2019

Sex, sensations and superstars

Founder and owner of 'Historieselskabet', Liv Thomsen, takes you back to a time when the whole world was on first-name terms with Asta, Clara and Valdemar.