The rise and fall of silent film’s brightest star

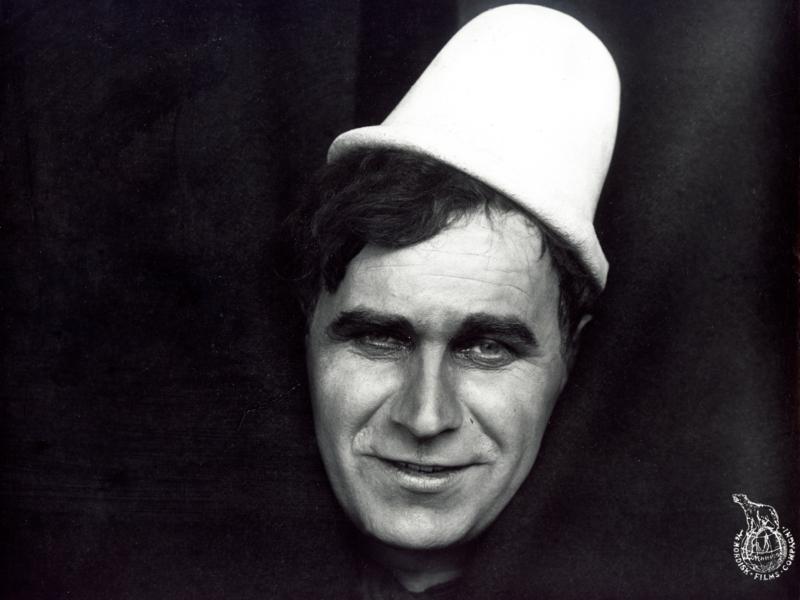

He was an idol to ardent female admirers around the world, in 1913–14 Russian and German film magazines proclaimed him their readers’ absolute favourite actor, his salary at Nordisk Films Kompagni was astronomical compared to the wages given to other actors, and he unapologetically demanded exorbitant raises. In return, the company profited just as much from his star status.

Lars-Martin Sørensen, Head of Research Unit | 9 December 2021

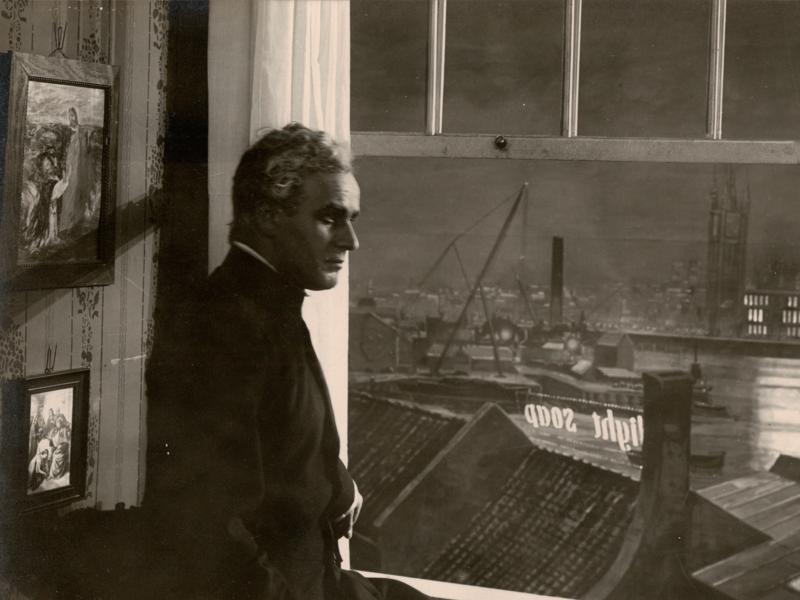

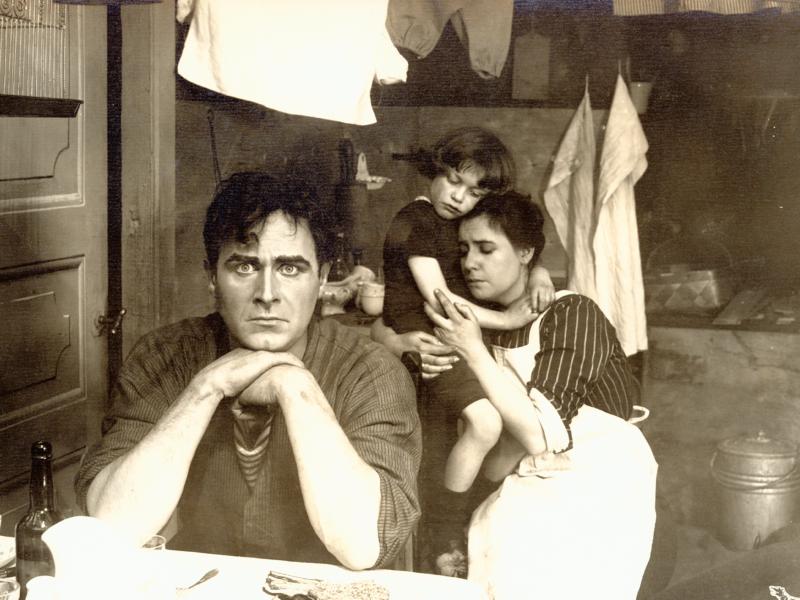

He made more than 83 films in just six years before he was found dead in his hotel room in Copenhagen at the age of 32. Valdemar Psilander became a world star in record time and died with just 10 kroner in the bank and 188 kroner in cash in his pocket. Like several fellow actors of his day, Psilander came from a Copenhagen working-class family where money was tight. His meteoric career in front of the camera took off after a somewhat unsuccessful attempt to gain a foothold in the theatre. But unlike Asta Nielsen, who had suffered the same fate on the stage and went on to pursue a great career in German film, Psilander stayed in Denmark and gradually attained what can confidently be called ‘global star status’ with Nordisk Films Kompagni in Valby as a base.

Before Asta and Valdemar firmly established their names as movie stars, they appeared together in The Ballet Dancer and The Black Dream, both from 1911. In the latter, Psilander hammed it up as a tragic leading man – a role in which he would since be cast time and time again at Nordisk. He made his film debut the year before with the small company Regia Kunstfilm, appearing in The Portrait of Dorian Gray alongside Clara Wieth – later Clara Pontoppidan. Someone at Nordisk Films Kompagni must have seen the potential in the thickset Valdemar, for shortly afterwards he was brought to Valby, where the company made a deliberate and concerted effort to market Psilander as a star – an unusual and groundbreaking initiative in the early 1910s.

Birth of an art form

Back when film production gained momentum after the founding of Nordisk Films Kompagni in Copenhagen and Fotorama in Aarhus in 1906, cinema – a brand-new invention at the time – was so widely despised as a mere flash in the pan that actors with theatrical ambitions insisted on appearing anonymously on film. As one of the pioneers, Storm P., puts it: ‘Back then, one could not be seen to be doing film; even a third-rate actor with the slightest self-respect spoke only derisively of the new invention’ 1. At the time around Psilander’s breakthrough – meaning 1910–11 – several factors changed radically. The arrival of the first multiple reel films, meaning films longer than 10–15 minutes, gave the audiences better opportunities for immersing themselves in the action, thereby establishing a rapport with the characters and actors. At the same time, the camera moved in closer on the actors, making facial expressions an effective and visible factor in film acting. The actors could be recognised from film to film, and the production processes were rendered more professional. At this point, film making becomes an actual industry with an official division of labour between screenwriters, set designers, directors, actors, etc., whereas in the infancy of cinema it was quite common for the director, lead actor and screenwriter – if there was any screenplay at all – to be one and the same person; at Nordisk Films Kompagni this was most frequently Viggo Larsen.

A star of many names

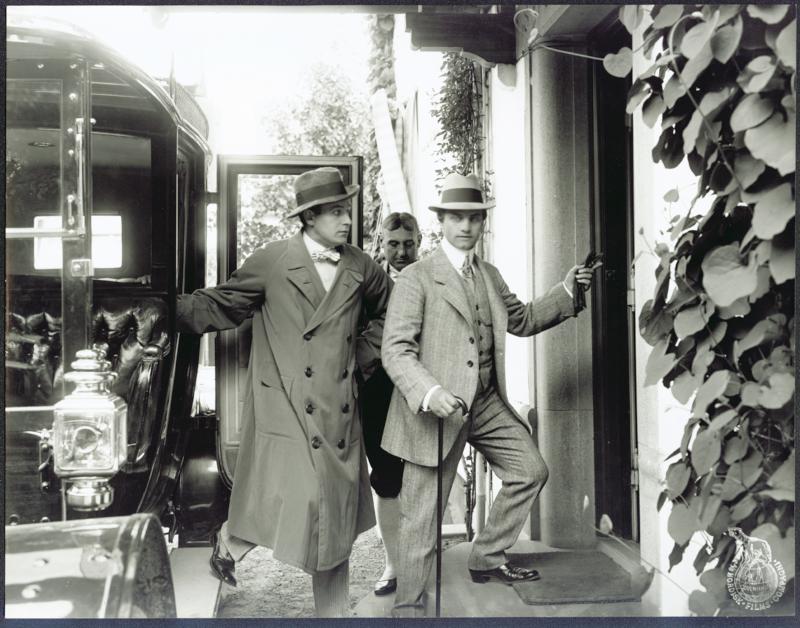

When Valdemar Psilander was hired by Nordisk in 1911, he soon fell into the capable hands of one of Danish silent film’s experienced and, later, great directors, August Blom. It is he who directs the breakthrough film Temptations of a Great City (1911), where Psilander gets to demonstrate his range – right from the outset, he is more than simply the heartthrob showcased in all the many parts of leading man in which he was subsequently cast.

The film became Psilander’s breakthrough as well as one of Nordisk’s biggest successes, and its smouldering on-screen kissing reached all the way to Brazil, where the Rio film magazines reported that the drawn-out kisses seen in Danish cinema were caused by the cold climate up north. After all, the residents there had to do something to keep warm. 2 Pronouncing Psilander’s name was something of a struggle in those parts, so here Valdemar occasionally went by the surname ‘Wuppschlander’, while in Russia he was quite simply marketed under the name ‘Garrison’. Valdemar Psilander suddenly had not just one, but several names. At the same time, other actors also began to be listed on the title cards of silent films. Clara and Carlo Wieth became major names, as did Olaf Fønss, Augusta Blad, Poul Reumert and Psilander’s wife, Edith Buemann Psilander. But none of them got as big as Valdemar, who reportedly received about 2,000 fan letters a year. Even the great diva, ‘Die Asta’, had to see herself relegated to second place when the above-mentioned German and Russian film magazines proclaimed Valdemar to be their readers’ favourite. Perhaps that is why she gave him the nickname ‘The World’s Valdemar’. And not long after the premiere of Temptations of a Great City, he was also the highest paid actor at Nordisk Films Kompagni. The company did everything they could to make Psilander a real movie star – including printing postcards and making little movie vignettes of him wearing a top hat and tuxedo. Valby’s take on a world-class star was Valdemar Psilander.

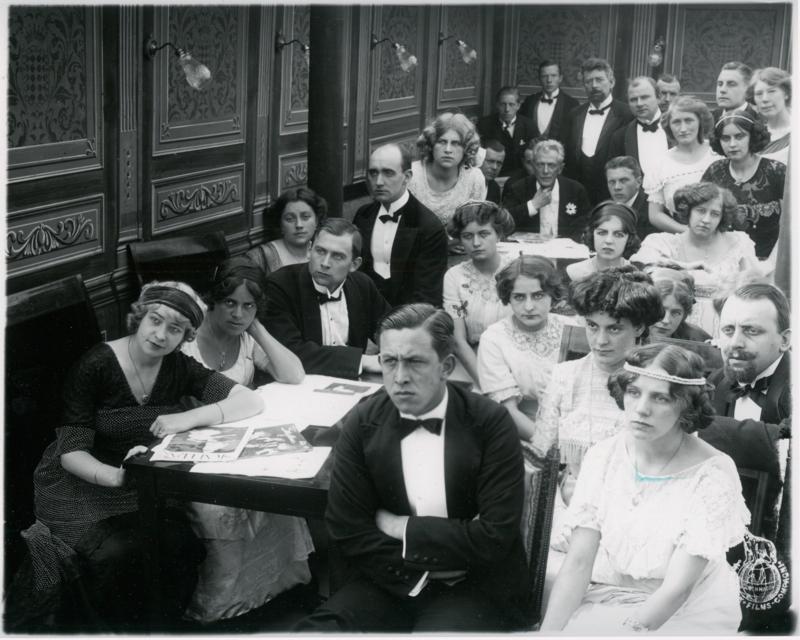

Valdemar and the rise and fall of the polar bear

Psilander’s career coincides with the star system having its international breakthrough. The Germans have ‘Die Asta’ and Henny Porten, the Frenchmen have Max Linder, Hollywood has Mary Pickford and Florence Lawrence and Denmark, which is among the largest producers in Europe at the time due to Nordisk Films Kompagni, has Valdemar Psilander. Ahead of the outbreak of the First World War, Nordisk proceeds at breakneck speed, presenting one Psilander showcase after another. Even the scriptwriting is specialised; now, Psilander’s own favourite author, Harriet Bloch, is preferred when choosing a new ‘Psilander script’. Or several scripts, to be precise. Due to Psilander’s high salary, the production management at Nordisk selected several scripts at once, ensuring that Psilander could go from shooting one film to the next without unnecessary interruption. He was given eight days to read up on his next role before filming began3. An immensely well-oiled machine was built up around the production of Psilander films. And the star seemed to thrive tremendously on all the hubbub – the stories and images of Psilander living it up and brandishing glasses of champagne are legion.

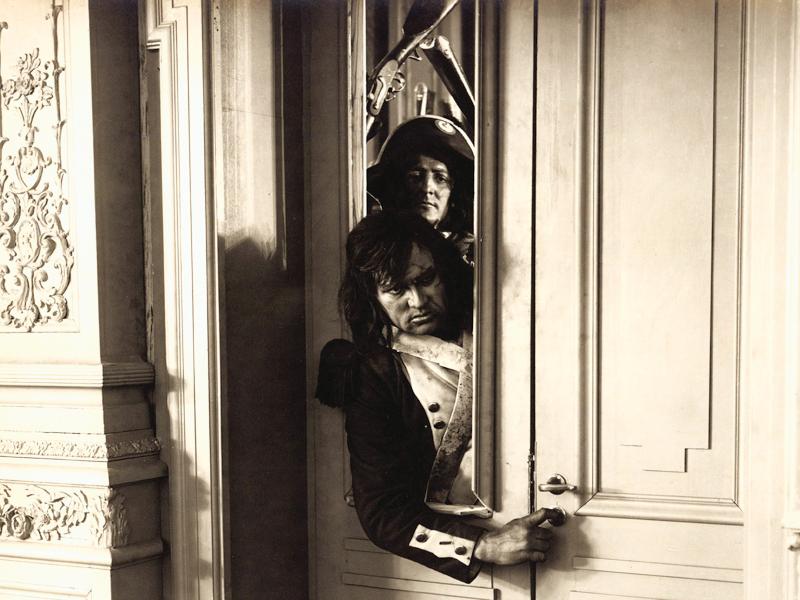

In 1915, his name had become so prominent that the film The Candle and the Moth begins with a vignette in which the star is shown allegedly seated at his desk, rehearsing his film role. The fact that the scene is a staged studio shot is as obvious as it is irrelevant: the introduction to the film serves to emphasise that this is a Psilander film, the use of moving pictures allowing the audience a quick glimpse at the great artist’s preparations ahead of what we about to see. Psilander makes notes in the script and leans thoughtfully back while a double exposure lets him also emerge in the picture as his character, John Redmond, in different phases of the film. We are inside the wizard’s very own workshop. And the magic happens at Nordisk Films Kompagni in Valby, where everything is going full steam ahead – well helped by the fact that Denmark has remained neutral in the Great War that broke out the year before. After all, being neutral means that you can sell your films on both sides of the fronts. The German-speaking Central European market is particularly effusive in its reception of Valdemar Psilander. Regardless of whether he plays a rough comedy cowboy on horseback in The Man Without a Future or a lieutenant in a dashing uniform in the war drama In Defence of the Nation – both from 1916.

But even though it is possible to make films about war and profit from it, nevertheless it is the war that pulls the rug out from Nordisk’s feet, ending its wild adventure as a major player in the European market. The company is hit by a boycott because it is perceived as pro-German by the Allies, and all the while it is also attacked by an increasingly war-nationalist industry press in Germany for not being German enough. In Denmark, Psilander severs his ties with the company and sets up his own, ‘Psilander Film’, because Nordisk refuse to give in to his increasingly exorbitant wage demands. On 6 March 1917, Valdemar Psilander is found dead in his room at Hotel Bristol in Copenhagen. Shock and speculation ripple through the Danish press. Was it suicide? Murder? Heart attack? Syphilis?4 Rumours are rife. Long obituaries are written all over the world; in Germany memorial performances are held, featuring lectures about Psilander; and in Russia a biopic about the Danish ‘Garrison’ is shot in a hurry. Nordisk has lost its first and biggest star. At the end of the First World War, the company’s huge portfolio of assets in Germany is nationalised. Psilander is dead. The polar bear’s decline is about to begin.

Posthumous profiteering and oblivion

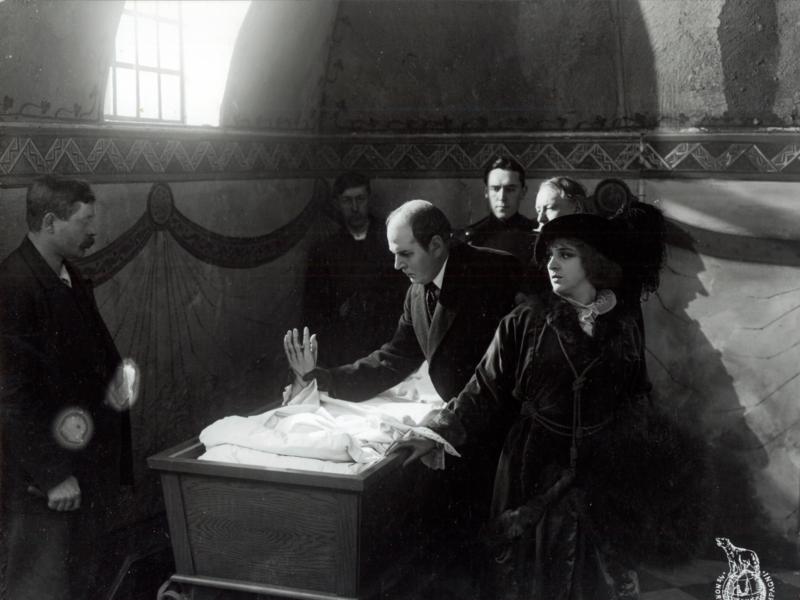

However, things do not go downhill right away, neither for Nordisk nor for Psilander’s popularity. After all, the most sure-fire way for a big star to attain mythological status is to die young. And two months after Psilander’s death we find the premiere of The Clown, probably the best film of his career. Here, Psilander is in the hands of the director who would go on to govern Nordisk’s image and direction during the next decade, A.W. Sandberg. Widely considered one of the absolute masterpieces of Danish silent film, The Clown is a resounding success – and Psilander’s death presumably played some part in this. What is more, Nordisk Films Kompagni has no less than twenty finished Psilander films sitting on their shelves, none of which had premiered at that point. The Valby company wastes no time in launching a major memorabilia offensive. The fact that Valdemar Psilander parted company with them shortly before his death is apparently of only minor importance. Memorial booklets are produced and sold, and right up until 1920 Psilander continues to generate posthumous profits for the company whenever new ‘Memorial films’ are premiered – to which we may add the various re-releases in the years that follow.

Even so, Valdemar Psilander gets no enduring, monumental fame in Denmark. Rather, he ends up in the nations’ collective lumber room with other forgotten flotsam and jetsam. Anyone who knows just one Danish silent film star is far more likely to remember Asta Nielsen than Valdemar Psilander – her iconic look, great talent and freshly relevant coolness factor makes Asta, who only made four films in Denmark, a far better-known Danish star than Valdemar today. Such are the vagaries of the collective consciousness, which is often more tinted by current agendas than the facts of the past.

Today, the guided tours at Nordisk Film in Valby include a visit to Valdemar Psilander’s wardrobe – a luxury bestowed on only few of the company’s actors.

On this site, we will upload an additional 24 movies to supplement the 17 films already posted online, thereby spreading awareness of ‘The Whole World’s Valdemar’.

Notes

1. Storm Petersen, Robert (1915). ‘Mine Teatererindringer’, part VIII–X. In: Masken, 27.6.1915, 252.

2. See Rielle Navitsky’s article on Psilander’s star status in Brazil: '”The Arbiter of Elegance”: Psilander’s Stardom and Elite-Oriented Film Culture in Rio de Janeiro' in Kosmorama #267 LINK

3. See Stephan Schröder’s article on Psilander’s customised scripts: 'Screenwriting for a Star: The Scripts for Valdemar Psilander’s Films' in Kosmorama #267 LINK

4. See Isak Thorsen’s article on Psilander’s death: 'Hjerteslag, syfilis, mord eller selvmord' in Kosmorama #267 LINK

Lars-Martin Sørensen, Head of Research Unit | 9 December 2021

Related articles

- Valdemar Psilander – A World Star in Danish Film Kosmorama #267

- Screenwriting for a Star: The Scripts for Valdemar Psilander's Films Kosmorama #267

- "Young Apollo, Friend of an old Damsel": Psilander and Finnish Film Culture Kosmorama #267

- Psilander, Dreyer, and Lydia Kosmorama #267

- Garrison, Star of the Russian Screen Kosmorama #267

- "The Arbiter of Elegance": Psilander’s Stardom and Elite-Oriented Film Culture in Rio de Janeiro Kosmorama #267