When Denmark Was Hollywood

Casper Tybjerg, Film Historian | 11 November 2019

Today, film and video are ubiquitous. It takes an active effort to avoid them. In the 1890s, however, “living pictures,” as they were known, were new and wondrous. In a few short years, film evolved into a new form of mass entertainment and a new art form. During this period, the pictures had no sound. It was only in the late 1920s that the necessary technology was developed to record and reproduce sound synchronised and amplified, and it was only when American movie studios saw a business advantage in the technology that sound films were ushered in. The period from the invention of cinema in the 1890s and up to around 1930 is the era of silent film.

Silent film as an attraction

The first living pictures were inherently appealing. Seeing reality reproduced with movement – photographs of trees with leaves fluttering in the breeze – was fascinating and enthralling. The new invention was soon featured alongside other attractions. Some of the first film screenings in Denmark took place in Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens amusement park. Films were soon on music hall playbills alongside singers and acrobats, or they were shown at markets and fairs next to lottery booths and shooting galleries. In the beginning, films were only around one minute long, and they often showed things that were spectacular in themselves: peoples in faraway lands, famous tourist attractions, dancers and acrobats, fire engines rushing to a fire, speeding trains, military parades and royalty.

The first films to be publicly shown – on Christmas Day 1897 – were Brandvæsnet rykker ud (The Fire Department Rushes to the Fire The Fire Brigade in Action) and Svanerne i Sortedamssøen (Swans in Sortedam Lake), filmed by Peter Elfelt, a court photographer who left extensive photo documentation of life in Copenhagen around 1900. As far as we know, the first film Elfelt ever shot was of the same type but with a more exotic subject: Kørsel med grønlandske Hunde / Driving with Greenland Dogs. Early cinema playbills also included more staged films, often small comical sketches, but over time more dramatic events, as well. In 1903, Elfelt made Henrettelsen / The Execution, inspired by a notorious murder case in which a French woman was sentenced to death and executed. Elfelt later said that he regretted making that sensational film.

Silent film music and colour

In 1904-5, cinemas began to flourish. Films had grown longer – 5 to 10 minutes, though never longer than 15 – and were usually included on playbills mixing films of different genres. Screenings were always accompanied by music. Music hall theatres had orchestras, while phonographs were sometimes used on fairgrounds. The first, small cinemas used to have a pianist, sometimes supplemented by a violinist or a couple of other musicians. The big palatial cinemas that were quickly put up in many major cities featured full orchestras. Films were still expected mainly to show spectacular events.

Often, the films were coloured. Actual colour film was invented around 1910, but these films were difficult to make and project. Instead, black and white film footage was coloured. The most common technique was tinting, or toning, where the positive print was dyed a specific colour depending on the action: night scenes were blue, sunny scenes were amber yellow, fire scenes were red, etc. The use of this was so widespread that film stock manufacturers even sold pre-dyed film. Ildfluen / The Firefly and Dr. Nicholson og den blaa Diamant / Dr. Nicholson and the Blue Diamond include scenes where the film changes colour several times during a dance performance to mimic the effect of changing stage lighting.

Occasionally, films were hand coloured by painting the individual frames one by one with a brush. Considering that a film has roughly 1000 frames per minute, hand colouring was extremely labour-intensive and ill-suited for mass production. An alternative was stencil colouring, where, instead of colouring frames in different colours one by one, a hole was cut in a filmstrip which was placed on top of the print. When the colour was applied, only the section inside the hole in the stencil strip was dyed. This was repeated with different colours as a way to mass-produce colour films.

Silent films as an entertainment industry

Stencil colouring was mainly used by the big French studios. French film pioneers recognised the potential of film as a mass media early on. With the Pathé film company leading the pack, film production became a real industry. Before the outbreak of World War I, Pathé, whose logo was the Gallic rooster, was the world’s biggest film studio.

The market for film was international. With no recorded dialogue, films were easy to export. Making title cards, intertitles, in different languages was easy and inexpensive. Moreover, the format had been standardised early on. In America, Thomas Edison’s lab, which had started shooting films as early as 1893, settled on a film width of 35mm (1 3/8 inches) with four sprocket holes per frame. Edison’s attempt to patent protect the format was dismissed by a court in 1902, and the format was free for anyone to use. In 1909, it became the official international standard for theatrical films. The format prevailed for a century, until digital projection replaced photochemical film in cinemas in 2010. The international nature of cinema made it possible for studios from small countries to compete.

In Denmark, Ole Olsen founded Nordisk Films Kompagni in 1906. At the time, cinemas were springing up in cities and towns around the world, and demand for new films was booming. Cinemas often changed their playbill more than once a week, and in some places every day. Seizing the moment, Nordisk in Valby grew into one of the leading film studios in the world. While Pathé picked the Gallic rooster for its logo, Nordisk opted for a polar bear atop the globe. Since bootlegging was a pervasive problem until the introduction of copyright laws for films, Pathé, Nordisk and other studios sought to protect their films by placing their logos directly within their films’ decorations.

Silent films as drama

In 1910, two smaller Danish film companies, Fotorama in Aarhus and Kosmorama in Copenhagen, enjoyed big hits with films of three reels, or three “acts” – that is, running 40-45 minutes, much longer than the 10-15-minute time that was the international norm. Both films – Den hvide Slavehandel (The white Slave Trade / The white Slave), of which only a small fragment still exists, and Afgrunden (The Abyss) – starred actors from the “real” stage, and both films titillated audiences with stories about sex and prostitution. The white Slave Trade is the story of a young woman who becomes a victim of sex trafficking, while The Abyss is a love drama set in an artists’ milieu. The Abyss’s two leads perform a dance number that is still strikingly erotic today, and Asta Nielsen as the female protagonist ends up stabbing her lover, played by Poul Reumert, when he wants her to prostitute herself.

Nordisk had an eye for the commercial potential of the feature-film format, and, starting in 1911, retooled its production to make all its dramas three-reelers of around 45 minutes, while the studio still used the short format for the comedies it was churning out alongside. Nordisk hired actors with stage experience, and romantic melodramas became a central genre. In Ekspeditricen (In the Prime of Life), the erotic attraction between Clara Pontoppidan’s shop girl and Carlo Wieth’s young man about town is palpable, while her pregnancy makes it plain that they had a sexual relationship.

The long dramatic films and the influx of stage actors caused many at the time to liken film to theatre. More sceptical voices scoffed at film as canned theatre: film equipment was just a type of recording and reproduction technology – as the gramophone is to orchestral music – not an independent art form. Moreover, they claimed, film lacked what they considered the core of the theatrical art: dialogue. Only the spoken word was capable of conveying spiritual content, which the sceptics saw as the task of all true art. Here and there, however, filmmakers and writers began to appreciate how the absence of dialogue was able to create a clearer and more intense experience of feelings, as expressed via poses and gestures, and in the interplay of face and body. Whereas the theatre had to accommodate for the distribution of the audience across a room with different sightlines and distances to the stage, the film image is the same for everyone. Because everyone is watching the action through the eye of the camera’s lens, visual composition, light and shadow and the actors’ movements can be used more precisely to capture and control the audience’s attention. Although the phrase “the silent art” was often used tongue-in-cheek in discussions at the time, it was proudly adopted by a lot of filmmakers.

Silent film as (un)culture

All the while, film production in the silent age was an unabashedly commercial affair. Filmmakers generally used hard-hitting effects to draw audiences. “Sensational films” is a genre description that first appeared in Denmark in the early 1910s, roughly corresponding to today’s action films. Whether dramas of crime or jealousy, these films should ideally include stunts on tall buildings or on top of speeding trains, as well as dangerous animals, explosions, car chases, even hot-air balloons and airplanes. Nordisk made a lot of sensational films, and Kinografen, a smaller studio, even specialised in the genre.

Moral guardians of the day looked with grave concern at film studios’ fondness for eroticism and crime, even if from today’s perspective it can be hard to see how the films could be seen as a threat to public decency. It is, however, fascinating to observe how the films deal with controversial subjects of the kind that even today trigger public debate. Moreover, the films inadvertently convey an impression of social interactions and expectations of how men and women should behave. Obviously, not only dress but body language has changed since then. The society that produced these films was plainly a class society with sharp divides between servants and masters, fancy folk and common folk.

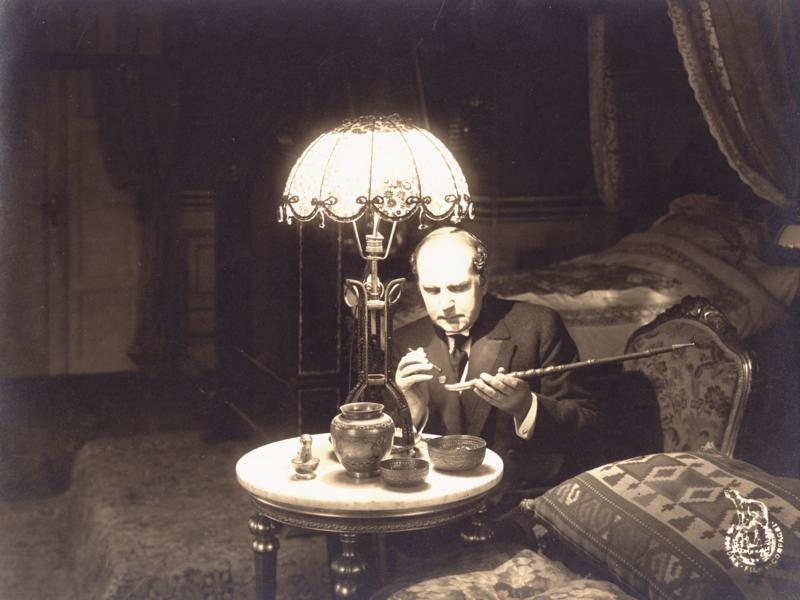

While some films show a clear social consciousness, others are less sober. The comedy Je’ sku’ tale me’ Jør’nsen (I want to speak to Johnson) presents its alcoholic protagonists as ridiculous and laughable. Drug abuse appears in both Dr. Nicholson og den blaa Diamant (Doctor Nicholson and the Blue Diamond) and I Opiumets Magt (In the Power of Opium), but in both cases as a purely melodramatic element. Unpleasant stereotypes sometimes rear their head: the facial features of an unscrupulous usurer in In the Power of Opium resemble anti-Semitic caricatures, and Løvejagten (Lion Hunting), a staged documentary about pith helmet-wearing big-game hunters, is clearly the product of a colonialist worldview in which it was only natural for Europeans to subjugate other continents and the people in them. And even though Charlottenlund Forest and the islet of Elleore in Roskilde Fjord stand in for Africa, the animals are actually killed on camera.

The diversity of silent films

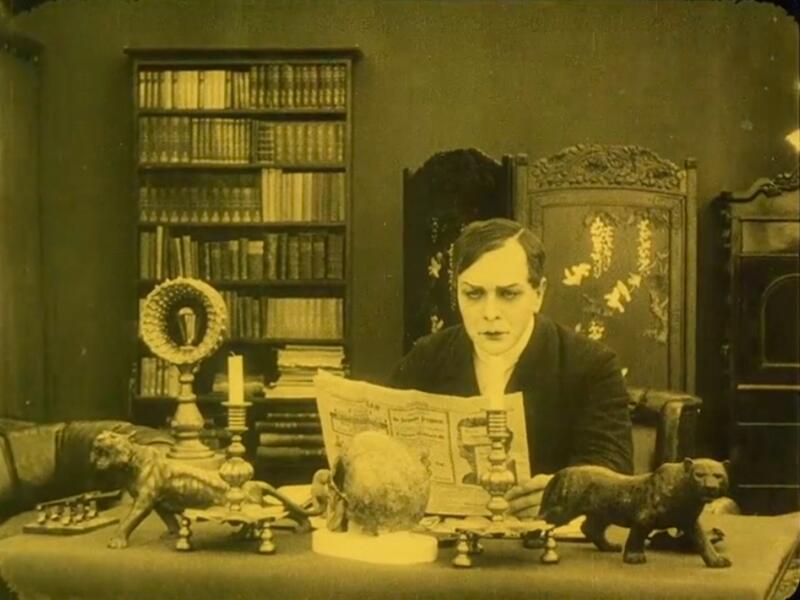

Despite the obvious differences between the expressive means of the silver screen and the theatre stage, there was still a tendency to see film and theatre as closely related media. In most European films before 1920, the inclination was to conceive each scene as a coherent whole and, in turn, present it in one extended shot. Scenes have very few cuts, and close-ups are rare. This is evident in both In the Power of Opium and Doctor Nicholson and the Blue Diamond, which cut to close-up only a few times to show a facial expression or a dramatically significant prop.

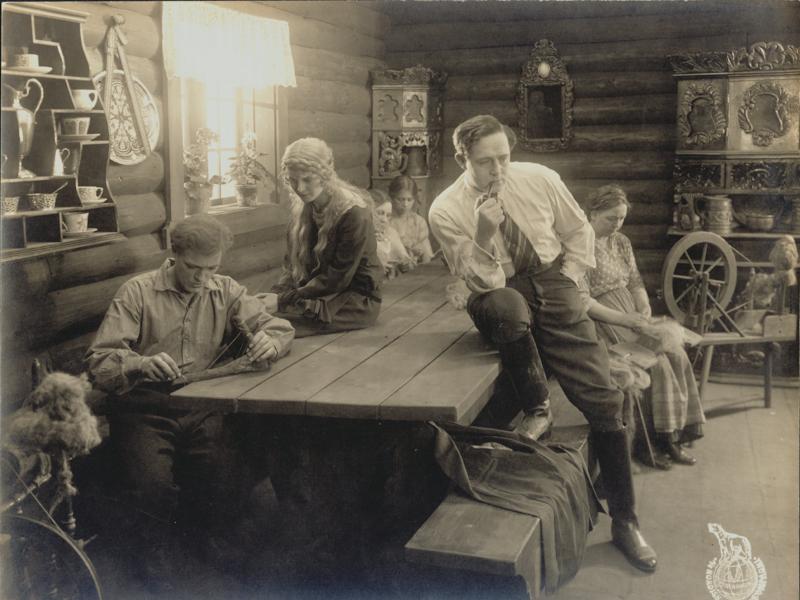

Influenced by American films, which started using cuts to guide the viewers’ attention and help them follow the action earlier than in Europe, the narrative style changes after the end of World War I, when American films flooded the European market and created the hegemony in global film that Hollywood has maintained to this day. Moreover, the increasing use of electric lighting instead of sunlight gives Danish films from the 1920s, like Lasse Månsson fra Skaane (Struggling Hearts) and Nedbrudte Nerver (The Hill Park Mystery), a more polished appearance.

The decline of Danish silent film

The above films were produced during a period that in many ways marked the decline of Danish film. During World War I, export markets were much more difficult to reach, and all the smaller Danish studios were forced out of business. Nordisk had foreseen the huge strategic challenge that Hollywood would pose after once the war was over, but, in part because of unfortunate external circumstances, their countermove failed, and the studio had to be significantly downsized.

In a brief period up to 1920, Swedish film enjoyed great success with masterfully directed dramas based on works by prominent Nordic writers and by employing Nordic nature as a backdrop and atmospheric element. Struggling Hearts and Morænen (The House of Shadows) can be seen as Danish attempts to recreate the successful Swedish formula.. They also underscore that silent film is not just one thing. Within a few short years, one-minute films showing dogsleds and folk life had evolved into features with the same running times as films today, fluidly told and acted with psychological insight and compressed emotional intensity.

While not an artistically groundbreaking work, Klovnen (The Golden Clown) from 1926 is a good example of a mainstream European entertainment film of the day. In terms of craft, it is fully on a par with the best products of the big film nations. There is not much Danish flavour – the film is aimed at an international audience. It is set in France and shot partly in Paris. The two leads are played by a Swedish and a French actor. Without dialogue, a mixed cast is no problem. The Golden Klown is a melodrama, a weepie about love and infidelity. Unashamedly sentimental, it nonetheless shows the undiminished power of the silent art to speak to the heart.

Casper Tybjerg, Film Historian | 11 November 2019