Carl Th. Dreyer in the silent era

Carl Th. Dreyer’s film career spanned six decades, and it all began with Danish silent film. This article analyses Dreyer's career and the significance of silent films for the development of his artistic ideas – for better or worse.

Casper Tybjerg, Film Historian | 13 December 2024

Early experiences with film

Carl Th. Dreyer began his working life by spending two and a half years as a clerk at Store Nordiske Telegrafselskab (Great Northern Telegraph Company). However, he found it dull and instead went on to become a journalist.

As a journalist, he first worked at Politiken, then Berlingske, followed by a stint at the short-lived newspaper Riget, and finally Ekstrabladet, where he gained particular attention for a series of irreverent and disrespectful profiles of Copenhagen celebrities, whom he enjoyed exposing as pompous and phony (only polar explorers and pilots escaped his scorn).

Almost simultaneously with securing employment at Ekstrabladet on 1 July 1912, Dreyer became involved in the film industry. He wrote the screenplay for the sensational film Dødsridtet (The Leap to Death), which was produced by Filmfabriken Danmark (or, more accurately, by the Skandinavisk-Russisk Handelshus, as the company was still called at the time). Dreyer was fascinated by aviation and, in 1910, may have been the world’s first international air passenger: he sat on the undercarriage of French pilot Poulain’s aircraft as it crossed the Øresund between Denmark and Sweden. He also undertook several hot-air balloon trips. His first film featured a balloon journey in which a carrier pigeon was sent off with an important message. Being an experienced balloonist, Dreyer handled both aspects.

In addition to The Leap to Death Dreyer wrote three more films for Filmfabriken Danmark, all of which are unfortunately now lost: Bryggerens Datter (Dagmar/The Brewer’s Daughter, 1912), Balloneksplosionen (The Hidden Message, 1913), and Krigskorrespondenter (War Correspondents, 1913). All four films were action dramas in which death-defying stunts played a crucial role.

Photo gallery: Dreyer’s various professions

In June 1913, Dreyer found part-time employment with Nordisk Films Kompagni. His responsibilities included writing and presumably translating intertitles for the company’s films, as well as drafting relatively detailed plot summaries for the souvenir programmes that accompanied most Danish films at the time.

Later in 1913 or early 1914, he wrote the screenplay for one of Nordisk Film’s most ambitious productions, the anti-war film Ned med Vaabnene (Lay Down Your Arms!). The film was based on a then-famous novel by Austrian writer and Nobel Prize winner Bertha von Suttner.

Learning the craft at Nordisk Film

By 1915, the task of adapting suitable novels became a regular part of Dreyer's job, and he ceased writing for Ekstrabladet. Most of the films made from Dreyer's novel-based screenplays are sadly lost. (A detailed description of one of them (Lydia, 1916) and an account of what written sources reveal about it can be found in the article Psilander, Dreyer, and Lydia, (Kosmorama #267)). Of Penge (Money), based on a novel by the world-renowned writer Émile Zola (filmed in 1914, premiered in 1916), only a fragment remains. It features Karl Mantzius, one of the era’s most respected theatre actors, in the role of the ruthless financier Saccard.

Dreyer did not only adapt novels by the much-lauded heavyweights of world literature. He also often reached for crime fiction: for example, the now-incomplete Rovedderkoppen (The Spider’s Prey) was based on a book by Norwegian author Sven Elvestad, who, under the pseudonym Stein Riverton, wrote a series of books about the master detective Asbjørn Krag, clearly inspired by Sherlock Holmes.

In Pavillonens Hemmelighed (The Mystery of the Crown Jewels), the central character is a master criminal played by Karl Mantzius, who also directed the film. He steals the crown jewels from a castle that is not explicitly identified as Rosenborg, though it is clearly recognisable.

In addition to his screenwriting work, Dreyer was also, according to his own account, involved in editing films for Nordisk Film. Alongside his work for the film company, he translated theatre texts and songs: Dreyer co-authored the Tivoli-Revyen of 1917 and, the year prior, he helped establish an open-air theatre in the Søndermarken park in Copenhagen.

Given all this, Dreyer was well-acquainted with many facets of filmmaking, acting and stagecraft when, at the age of 29, he directed his first film, Præsidenten (The President).

Inspiration from America

The President was based on one of the novels Dreyer had recommended to Nordisk Film, suggesting that it should be acquired for adaptation. The film emphasises its veneration for its literary source, written by Austrian author Karl Emil Franzos, by both beginning and ending with the book. However, whereas the novel’s narrative is very clearly tied to a specific location and period within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Dreyer sets the film in a more vaguely defined Central European setting, focusing on the characters’ moral choices and on universal human themes of guilt and redemption.

The film’s main protagonist is a court president, a judge who must pass sentence on a young woman who faces the death penalty for murdering her newborn child after being abandoned by the man who seduced her. The judge realises that the young woman is his illegitimate daughter, born after he abandoned her mother because her family was not of sufficiently high social standing for him to marry her. Dreyer tells the story in a way that makes it clear to the viewer that the young woman is blameless, but also that no good solution exists to the titular court president’s moral dilemma: he saves his daughter but in doing so violates the law to which he has dedicated his life, leaving him burdened by guilt he cannot bear. While some plot elements are highly melodramatic, the overall impression is of a film that ranks among the most psychologically and morally complex of its time.

The film is also stylistically groundbreaking. As has been demonstrated by the renowned American film scholar David Bordwell, Danish films of the 1910s primarily used what later film historians have termed the tableau style: each scene was typically composed of a single long shot with the camera positioned relatively far from the actors. The viewer’s attention was then guided towards the elements pertinent to the plot by the composition of the frame and, especially, by the arrangement of the actors and how they moved in relation to one another within the space. Bordwell points out that Dreyer takes a different approach in The President. He makes far more extensive use of editing to direct the viewer's attention. Scenes that, in other Danish films of the period, would typically have been depicted in a single long, carefully arranged shot, are instead broken into a series of individual shots by Dreyer. The approach is particularly apparent when comparing the beginning of the court proceedings in The President with, for example, the courtroom scene in Af Elskovs Naade (Acquitted, 1914), where the entire trial unfolds in a single, carefully arranged deep-focus shot that captures the accused, the defence lawyer, the prosecutor, the judges, witnesses and spectators in a single frame. Only when Betty Nansen, playing the accused, gives her testimony is the camera moved closer.

In contrast, Dreyer arranges his characters in a much wider, flatter space where it is impossible to see everyone at once, instead cutting freely between the individuals involved.

Dreyer had clearly studied American films and grasped the potential of their far more extensive use of editing to guide the viewer’s attention.

Dreyer’s visual compositions also deviate from the norm. He later spoke of how he greatly admired the artist Vilhelm Hammershøi’s paintings at the time, and this is evident in several of the film’s interior scenes. Dreyer also found atmospheric locations for his exterior shots: many scenes were filmed in and around Visby on Gotland, giving the film a distinctly non-Danish appearance, though Danish locations such as the manor house Liselund on the island of Møn are also featured.

Parting ways with Nordisk Film

The President was so successful that Dreyer, at a time when the financially struggling Nordisk Film was parting ways with several of its experienced directors, was given the opportunity to create a truly grand production. Blade af Satans Bog (Leaves from Satan’s Book) was one of the most expensive films ever made in Scandinavia at the time. It is divided into four episodes, all following Satan, who is condemned to tempt humanity into sin and deceit. Unlike most of Dreyer’s works, the film was not based on a literary source but on an original screenplay by playwright Edgard Høyer, first submitted to Nordisk in 1913.

The film’s structure appears to have been borrowed from the Italian epic Satana (1912), directed by Luigi Maggi, of which sadly only short fragments survive. However, press reports from the time informs us that Maggi’s film also consisted of four parts, each set in a different historical period and depicting Satan pursuing his evil endeavours.

In Dreyer’s version, the four eras are: the time of Jesus, sixteenth-century Spain during the Inquisition, the French Revolution, and the Finnish Civil War in the spring of 1918. For the first three episodes in particular, Dreyer conducted extensive studies of art and historical depictions to make everything as authentic as possible. His handwritten notes in the script reference images in books used as templates for props, costumes and shot compositions. Dreyer also continued to develop his use of editing as an expressive tool, often cutting between multiple narrative threads within the four epochs.

The cinematography was handled by George Schnéevoigt, and Dreyer was so pleased with their collaboration that Schnéevoigt went on to shoot three more of Dreyer’s films. Schnéevoigt’s camera work is densely atmospheric, subtle, yet highly plastic in its lighting, and crisply detailed in the many close-ups throughout the film. It also incorporates sophisticated technical flourishes that were highly unusual for the time. For instance, in a scene from the third section (the French Revolution), in which disguised aristocrats arrive at an inn and ascend a staircase to their rooms, Schnéevoigt adjusts the focus mid-shot, shifting attention from the disguised aristocrats in the foreground to Satan, who stands at the base of the staircase observing them.

Despite its qualities, Leaves from Satan’s Book ultimately led to a break between Dreyer and Nordisk Film. Although the film was exceptionally expensive, Dreyer wanted additional, very costly scenes. The management at Nordisk refused and put their foot down, prompting Dreyer to respond with a long, indignant letter to managing director Wilhelm Stæhr:

I will not agree to cut corners just so the film can ‘slide through’, for I would be nothing less than a callous scoundrel if I – merely to secure a director’s fee – agreed to make a film which, according to my innermost conviction, can only turn out to be a third- or fourth-rate production.

(Letter from Dreyer to Wilhelm Stæhr, 23 March 1919, reprinted in Kosmorama 85, June 1968.)

Instead, Dreyer suggested that Nordisk should let a Swedish company take over the entire production, a proposal which the director-general of Nordisk, Ole Olsen, unsurprisingly rejected. Dreyer had signed a contract, and he was obliged to complete the film. He duly did so, but afterward he had to continue his career elsewhere.

Art and chamber plays

In Sweden, film production was experiencing a brief golden age. Directors such as Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller won international acclaim for their masterfully crafted films, several of which were based on works by renowned Nordic authors and featured Nordic landscapes and folk culture as essential elements. Dreyer’s Swedish-produced Prästänkan (The Parson’s Widow, 1921) closely followed these Swedish models in terms of style. The film tells the story of a young man who, in order to secure a parish post in seventeenth-century Norway, must marry his predecessor’s much older widow. He passes off his fiancée, who is his own age, as his sister, and Dreyer portrays the impossible situation with great sensitivity. To ensure that the settings were as authentic as possible, Dreyer went to great lengths to shoot the film on location at the open-air museum Maihaugen in Lillehammer. In 1926, Dreyer made another film that clearly adhered to the Swedish model: the Norwegian production Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal).

During the remainder of the silent film era, Dreyer’s career largely unfolded abroad. However, he did make two more films in Denmark: Der var engang (Once Upon a Time, 1922) and Du skal ære din Hustru (Master of the House, 1925). The first was based on Holger Drachmann’s National Romantic play and produced by cinema owner and distributor Sophus Madsen, who had close ties to the Swedish film industry. With its nationalist theme, acclaimed source material, and densely atmospheric images of Danish forests, Once Upon a Time was in many ways an attempt to transplant the qualities of Swedish films onto Danish soil. Sadly, the surviving copy of the film is incomplete: several scenes and the entire final third are missing. While this makes it difficult to fully evaluate the film, it can reasonably be said that the film lacks some of the psychological depth and sensitive human portrayals that characterised the best Swedish films. This is perhaps not surprising, as Drachmann’s aggressively male-chauvinistic fairy-tale drama hardly provided the best foundation for such qualities, even though Dreyer’s adaptation is gentler and leaves out the most glaring aspects of Drachmann’s original work.

Before Once Upon a Time, Dreyer had made a film in Germany, Die Gezeichneten (Love One Another, 1922), which, with striking realism in its depictions of its settings, describes the persecution of Jews in Tsarist Russia and compellingly warns against the scourge of antisemitism. He later returned to Germany to shoot Mikaël (Michael, 1924), based on Danish author Herman Bang’s novel. This film tells the story of an ageing painter and his unrequited love for a young man who is both his model and protégé; it is notable for its nuanced portrayal of its characters and its discreet yet for its time obvious depiction of homosexual love.

When Dreyer returned to Denmark, he worked for Palladium. Master of the House was based on a popular stage comedy by Svend Rindom. The film can rightly be called a chamber play, a term Dreyer himself used to describe it. In this film, the emotional significance of its editing is also evident. By continually cutting between the characters, Dreyer highlights what they see – and do not see – and how they react to it. We perceive how little the husband sees, how much of a burden this put on his wife, and how clearly the old nanny, Mads, perceives that something needs to be done.

The sensitivity with which Dreyer stages the film is also supported by his actors. As both film art and a study of humanity, Master of the House became a pinnacle of Danish silent film.

In the wake of the silent film era

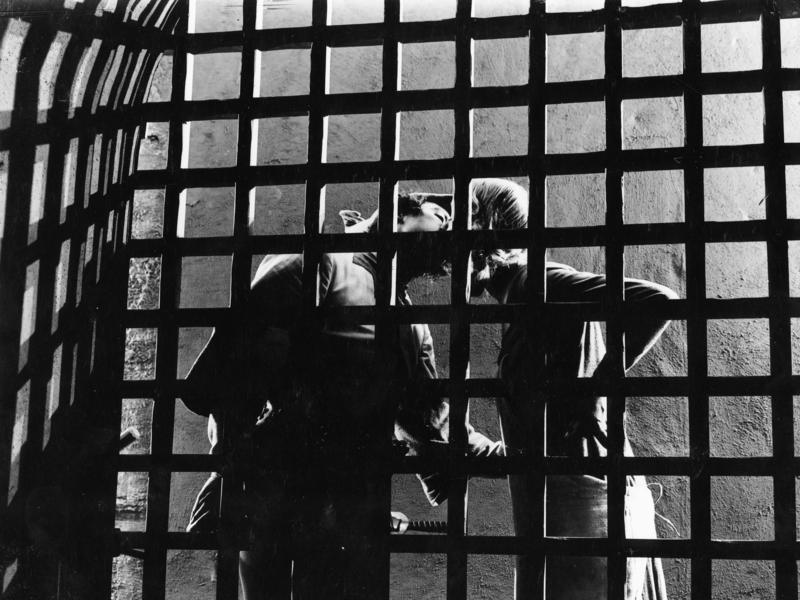

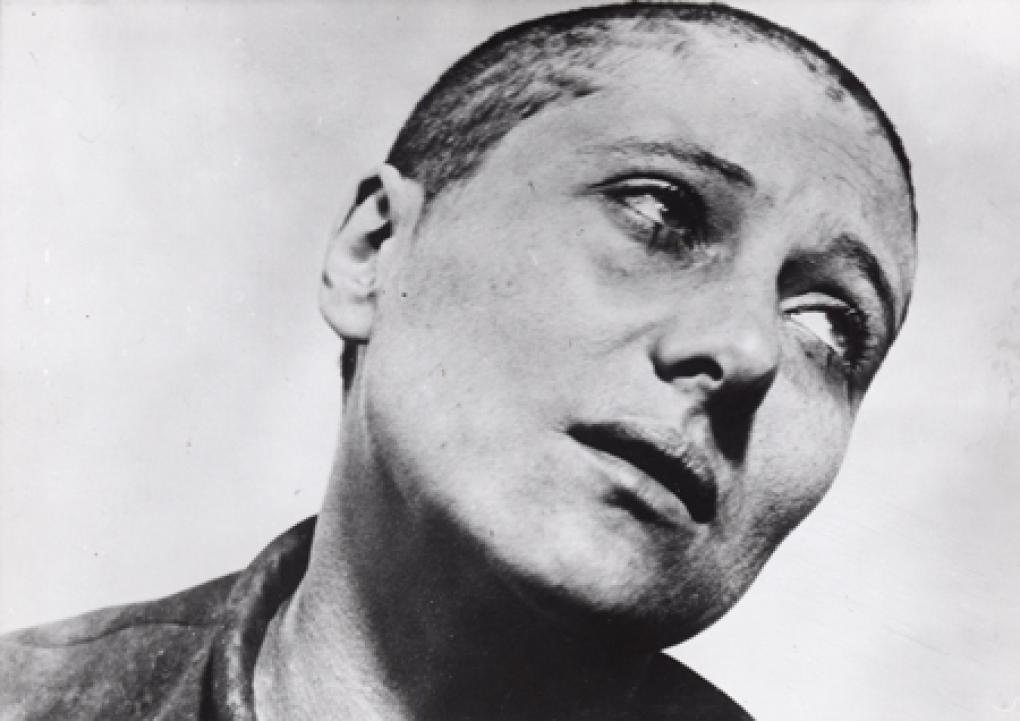

In France, Master of the House was a great success and paved the way for Dreyer’s last silent film, La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (The Passion of Joan of Arc, 1928), a film that completely lacks establishing shots and fractures the narrative into a continuously shifting sequence of faces and reactions.

Dreyer’s first sound film, Vampyr (1932 [filmed in 1930]), was originally planned to also be released as a silent film. Dreyer long clung to the idea that silent film offered a unique artistic form of expression that could live on alongside sound film. However, that hope proved futile, and Dreyer’s career came to a halt.

When Dreyer returned to filmmaking after a hiatus of more than ten years with Vredens Dag (Day of Wrath, 1943), several reviewers criticised the film for resembling a silent film. Dreyer strongly rejected this claim:

It has been said that the tempo of my film is akin to that of the silent film era. Quite the contrary! That time was characterised by the buzzing, rapid pace at which scenes dashed across the canvas, and I have consciously and deliberately sought to establish a sense of calm in the scenes that suits sound film, allowing impressions to settle and take root. I have experimented my way to creating a visual effect and approach to scene transitions that can only be combined with sound film and have nothing to do with silent film. (‘If I were to make the film again, it would be just the same’, interview, B.T., 17 November 1943.)

And it is true that, while in his silent films – whether created in Denmark or abroad – Dreyer had relied heavily on editing as a means of expression, his last four sound films from Day of Wrath onward saw him develop a mode of expression based far more on long, lingering shots, often with a moving camera. In these, actors positioned themselves in relation to one another and changed positions according to a meticulously choreographed plan.

When Dreyer speaks of the ‘buzzing pace’ of silent film, he is likely referring particularly to the films of the late 1920s, where the editing tempo was indeed often very rapid. For his final film, Gertrud, he chose instead a style that not only aligned with his ideas of the calm tempo suited to sound film and to tragedy but also evoked the style of films from the 1910s – a period close in time to the film’s source material, Hjalmar Söderberg’s play Gertrud from 1906. The film was produced by Palladium but shot in Nordisk Film’s studios in Valby, where the company had rented space. In this way, Dreyer, with his final work, can be said to have returned both stylistically and physically to the place that had been the starting point of his cinematic career.

The films

Explore the Dreyer website

Visit Kosmorama