They rose high and fell hard, the daredevils among the silent film era’s actors, stuntwomen and stuntmen as they performed spectacular and at times downright life-threatening feats of foolhardiness in the pursuit of new, sensational hits. We have picked out a handful of derring-do moments from back when cinema’s close kinship with sword swallowers, bearded ladies and other carnies was easy to spot. Long before the days of health and safety regulations.

Lars-Martin Sørensen, Head of Research Unit | 24 April 2024

Faster, higher, crazier …

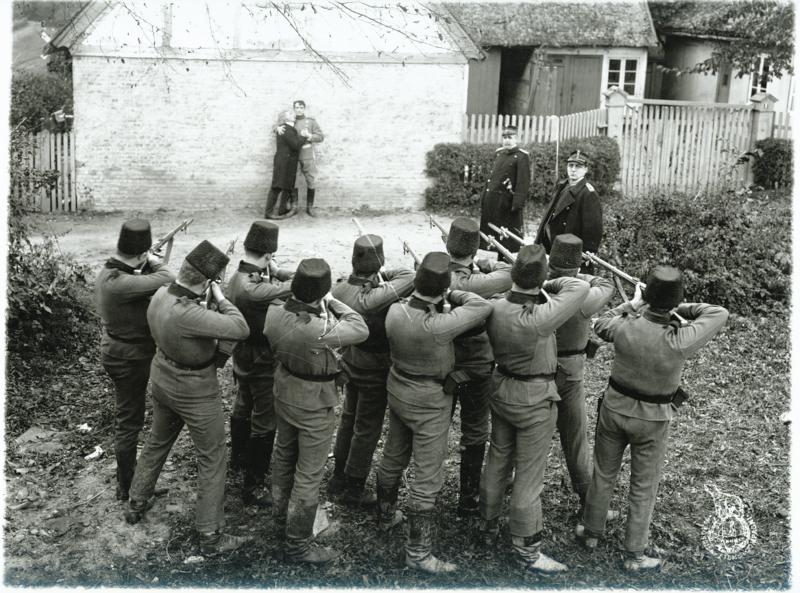

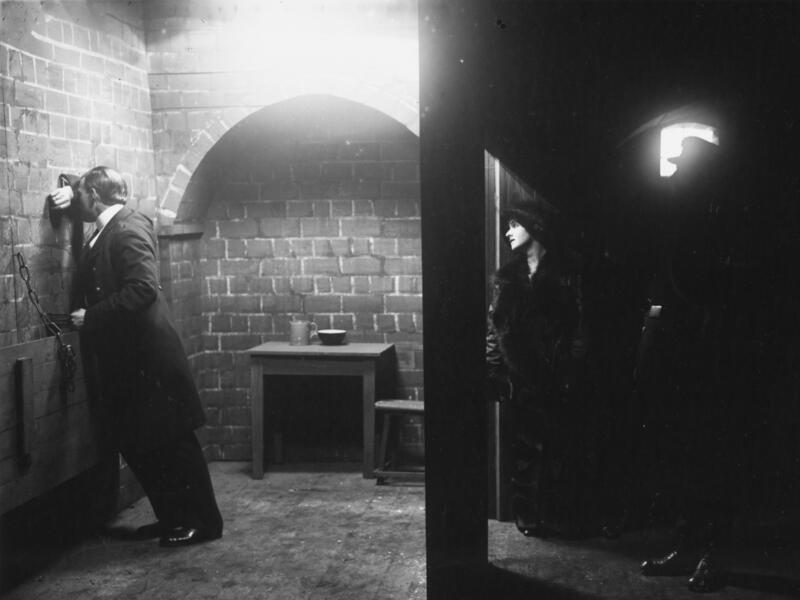

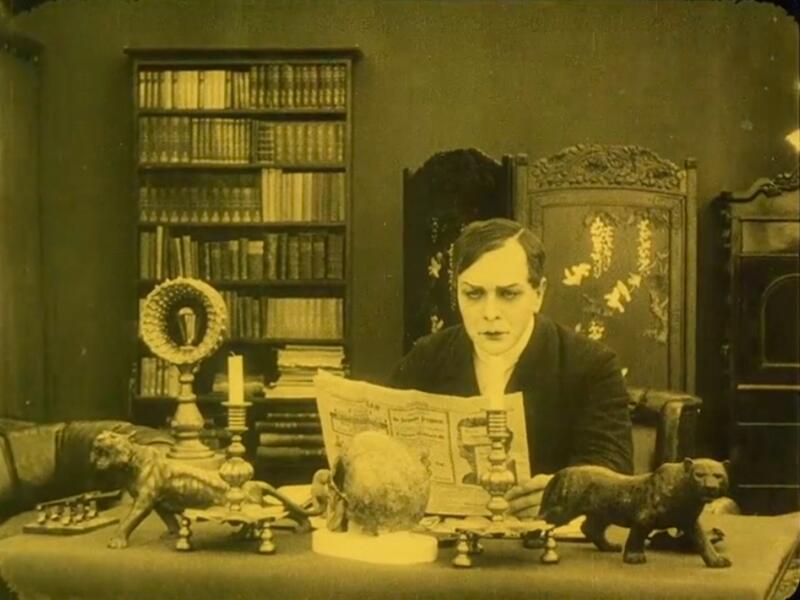

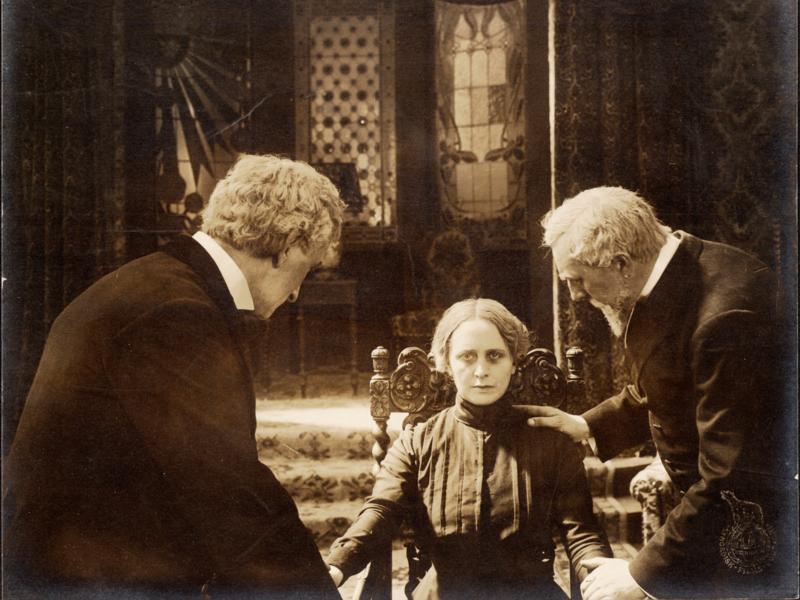

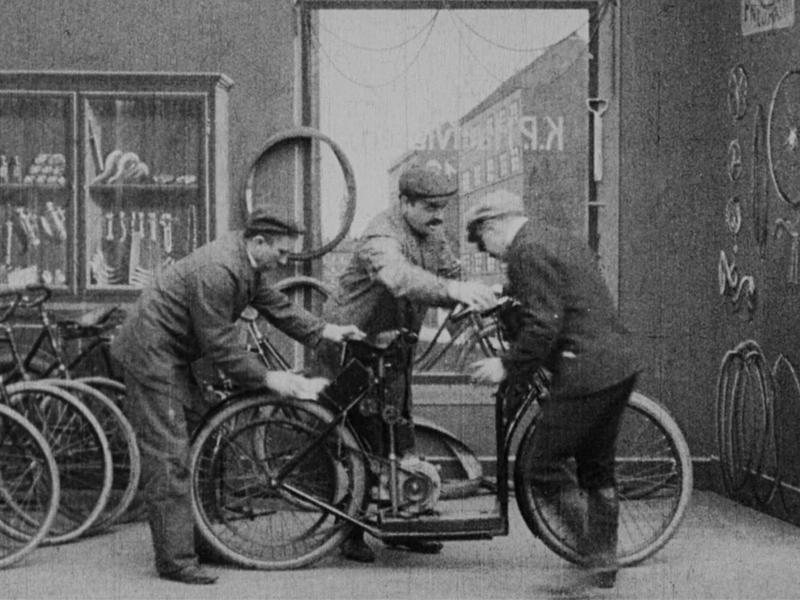

All sorts of mad things began to happen in Danish cinema in the early 1910s. The happy-go-lucky, anarchic pioneering days when all that was needed was to have something – anything – move in the pictures were long over. A longer film format capable of unfolding dramatic narratives quickly became the standard. Large companies such as Nordisk and Fotorama particularly excelled in this field, being able to afford theatre-trained actors. Smaller companies and the slightly larger SRH/Filmfabriken Danmark saw the potential of a different type of cinema: the ‘sensational film’. The recipe for such a film was simple: just devise the wildest, most dangerous and most sensational stunts imaginable. ‘The actor must either place himself among wild animals, or he must carry out jumps or climbing feats that put him at risk of plummeting from great heights, or leap from or to various means of transport at full speed’, explained director Urban Gad in the first Danish book om film theory, Filmen – Dens Midler og Maal (Film – Its Means and Ends) from 1919.

There is plenty of jumping on and off means of transport at full speed in the action-thriller Dr Nicholson and the Blue Diamond from 1913, named after its pallid villain. Here one finds car chases (Clip 1) enacted at the greatest breakneck pace achievable with the automobiles of the time, and a deadly leap from a train at full speed as it moves across a bridge. This jump is so high and fast that the jumper, who is seen from behind and the side from a long distance during the actual feat, is unlikely to be the actor Holger Reenberg, who plays Dr Nicholson; rather, it would have been a now-unknown stuntman (Clip 2). As the antics at the various film studios grew in scope and scale, risking one’s life in the service of cinema became a way of making a living.

|

Dr Nicholson and the Blue Diamond (1913) |

|

| Clip 1 | Clip 2 |

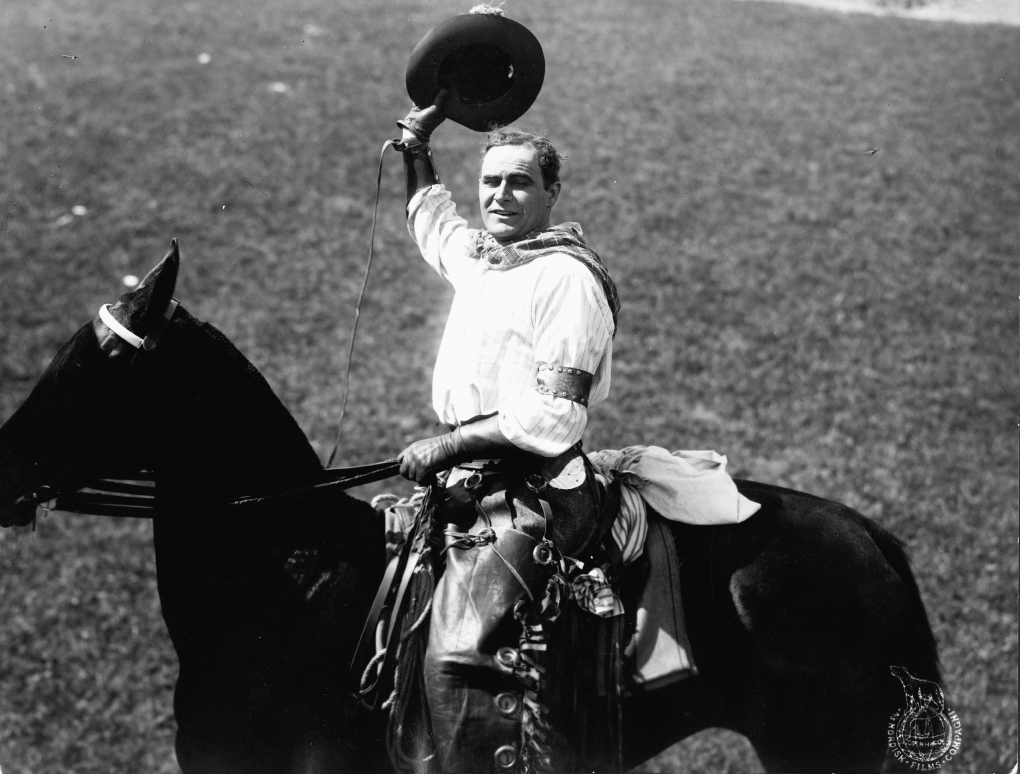

A fatal jump in a circus dome

Among those who made ends meet as a stuntman we find the Swedish-born horse trainer Axel Mattson, whose riding school and stables still exist today in Klampenborg at the entrance to Dyrehaven. Mattson was a close friend of the biggest film star of the 1910s, Valdemar Psilander, and acted as a stand-in for the superstar on several occasions, including in the ‘sensational film’ known by several adrenaline-charged titles: ‘The Great Circus Catastrophe’, ‘The Platform of Death’ and ‘A Fatal Decision’ (1912). Here, a bankrupt count, played by Psilander, falls in love with a circus princess and ventures to perform a mad stunt to impress her: on horseback in a rather rickety wooden frame, he is hoisted high, high up under the circus dome to jump deep, deep into the arena. The jump proves fatal. In the movie, that is. During filming, Psilander, who is first seen on his way up, is replaced by Mattson, who then performs the death jump. Mattson is seen from behind just before the big jump and from the side during the leapitself (Clip 1). According to the press of the time, Mattson was so badly injured that he had to have a silver plate implanted to repair the damage done to his skull by the hard landing in the arena. Still, he allegedly received a fee of 500 kroner and an inscribed wine carafe for his troubles.

| The Great Circus Catastrophe (1912) | |

| Clip 1 | Clip 2 |

Psilander himself was no coward when it came to performing lethal scenes. In the same film, he defies all fire safety advice by riding a lift in a burning house, then climbs onto the roof and walks across to the neighbouring building on telephone wires (Clip 2). A perhaps even more daring deed is the rollercoaster ride undertaken by Psilander – once again to impress a lady, this time an eccentric countess – in the film ‘Vanquished’ (1912):

| Vanquished (1912) |

| Clip 1 |

A python on a tightrope

‘Sensational films’ had a pronounced kinship with the realm of carnival performances and circus artistry. In the early 1910s, Nordisk Films Kompagni responded to this affinity by building a permanent circus stage where artists would carry out various daring stunts with wild abandon. Several of the films of the time were about circus performers and acrobats, for example ‘In a Den of Lions’ (1912), where a tight-rope walker plummets into a tiger cage (Clip 1) and an aerial acrobat falls through the safety net: obviously, such precautions need to malfunction when they are needed the most – otherwise there would be no sensation! (Clip 2).

| In a Den of Lions (1912) | |

| Clip 1 | Clip 2 |

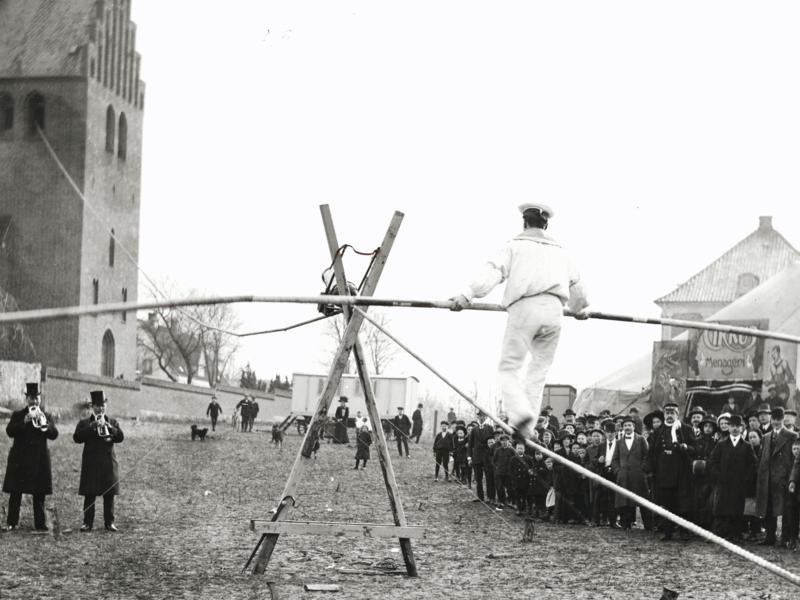

One of the early masterpieces among the ‘sensational films’ is ‘The Pride of the Circus’ (1912). Here, a tightrope walker from a travelling circus seeks to become rich enough to marry the mayor’s daughter, and he intends to do so by walking a tightrope to the top of a church tower. As fate would have it, a vast python belonging to his spurned former girlfriend, a snake charmer, has escaped and is heading down the tightrope as he is making his ascent. It is hard to imagine anything more perfectly calculated to produce an exhilarating effect: a duel of balance between a tightrope walker and a python played out at the dizzying height of a church steeple! However, on closer inspection the scope of that height turns out to be somewhat mutable. As the tightrope walker moves up the rope, we take in the vertiginous sight of the tall tower of Brønshøj church. We also look down the rope and see how the people down on the ground appear smaller and smaller. But once the tightrope walker approaches the tower and encounters the snake, the shot suddenly includes some rather intrusive branches of trees that did not grow by the Brønshøj church in the previous clip. The explanation is simple: the second part of the sequence, involving the python, was filmed at another tower, namely in Kalundborg, where the terrain slopes steeply down towards the harbour. This makes the view from the tightrope and tower seem even more dizzying, although the illusion makes it look as if there is further down than is actually the case – we are at the height of treetops, not church steeples.1

| The Pride of the Circus (1912) |

| Clip 1 |

Pythons held a magnetic fascination for audiences in themselves, a fact that was also exploited in the marketing of the film. Shortly after the premiere, the newspaper Politiken reported that the snake was on display in front of the Victoria Theatre, but...:

Last night, the serpent began to stir, seeking to escape, and the great snake actually succeeded in smashing the glass roof above its prison by pushing its powerful back against it. A moment later, it entered the film theatre itself and was heading for the street when solo dancer Richard Jensen, who is famously the snake’s opponent in the film, arrived and saved the day. Fearlessly, he grappled with the beast, and despite its eager resistance and determined attempts to strangle him, the solo dancer triumphed once again, as in the film, and eventually put the serpent back in its box. Now, sufficient precautions have been taken to render any new escape attempts quite futile.2

Whether the story is in fact true or merely an obvious marketing ploy must remain a matter of conjecture. We do, however, know that the snake sold plenty of tickets.

‘If death comes, it comes’

The one person to most fully embody the daring boldness of the time was Emilie Sannom, who was a fixture in Filmfabriken Danmark’s ‘sensational films’ up through the 1910s. In numerous films, Sannom’s stunts were the main attraction, winning her the nickname ‘Daredevil of the Movies’. This was also the title of the cavalcade of stunts she put together in the 1920s in order to have something to show when giving talks about her film career, which was over by that time. In the showreel we see her coming down a windmill sail from a great height (Clip 1), walking on a loosely swinging rope without a safety net (Clip 2), balancing on spiky glass lamps (Clip 3), climbing a church steeple and swinging cheerfully on a church bell – while wearing high-heeled platform boots too, hardly a suitable choice for climbing (Clip 4).

| Daredevil of the Movies (1923) | |

| Clip 1 | Clip 2 |

| Clip 3 | Clip 4 |

Sannom’s particular party piece was aerial acrobatics and parachuting, and she toured with these acts when her film career ended around 1920. Often wearing frothy, skimpy outfits, she would dangle from the plane’s landing gear, crawl around on the wings and throw herself from a great height while donning her parachute mid-fall (Clip 5):

| Daredevil of the Movies (1923) |

| Clip 5 |

She consciously cultivated her image as wild and fearless, her sass and swagger coming hard and fast in numerous interviews: ‘... I had to watch out for the propeller. It was only half a metre from me. If I got too close, it would be like ending up in a meat slicer!’, she confided to the journal Tidens Kvinder in 1929, going on to assert that ‘I am in my element when I am in an airplane, hanging from one wing, on the back of a horse or out at sea when it shows its foamy teeth. I get seasick from being indoors.’

Still, even a self-proclaimed daredevil has her worries. In an interview with one of the newspapers of the time, Sannom said: ‘I am very afraid of one thing: the parachute, it is terrifying, I am at the mercy of its whims. I trust the airplane implicitly, but the parachute …’ Indeed, the parachute would eventually be the death of her. In the summer of 1931, Sannom crashed to the ground from a height of 600 metres during a show on Djursland where the parachute failed to deploy. According to several newspapers, her body burrowed itself several feet into the ground. Twelve years before, she had faced danger and death with a nonchalant shrug in the women’s magazine Vore Damer: ‘Life is not worth living without excitement, and if death comes, it comes ...’.

From the extreme extremes of storytelling

The ‘sensational films’’ frenzied pursuit of spectacle and excitement was met with indulgent scepticism from several film critics of the time. When sensational stunts become the focal point, there are rarely compelling reasons to exert much effort on the story itself. In the ambitious ‘gypsy film’, as they were called at the time, Raphael, The Gypsy (1914), a jealous Emilie Sannom – wearing a ‘gypsy’ outfit – ties her rival to a reindeer and drives the animal across the moor so that her adversary is dragged away, first through the heather, then across Hald Lake, and then finally ashore through swamps and reeds (Clip 1):

| Raphael, The Gypsy (1914) |

| Clip 1 |

The unfortunate Zanny Petersen, the actor being towed along, appears most uncomfortable as the involuntary appendage to a reindeer in those scenes where it is not just a rag doll being dragged around. Things brighten up when her beloved completes his simultaneous struggles through sluice gates, reeds and lake water, and the soaking wet, miserable and undoubtedly rather battered lovers are finally reunited. Ekstrabladet’s verdict read:

All the horrors that can possibly be conjured up by a cunning film director are in evidence in this gypsy feature, in which Filmfabriken Danmark’s most outstanding actors display all their talents and all the fearlessness and agility that have built the reputation of, for example, Ms. Emilie Sannom and Mr. Em. Gregers among film audiences who have a taste for impressive spectacles and effects.

Never mind, then, that the plot is contrived and improbable: the audience that adores the thrill of such films wants to see their heroes and heroines cope with the most terrible perils and traps with a smile, wants to see them brave and noble, or cunning and villainous to the extreme.3

In some cases, not only the plot but the sensation itself is batshit crazy. One example is found in ‘The Impostor’ (1918), where a driver wearing very obvious blackface starts a car and drives across a bridge, which collapses, whereupon the car – completely and utterly inexplicably – explodes in a cloud of smoke. Or a scene featuring the dashing leading man jumping from the first floor of a building to land on a pile of logs, where he passes out and is propelled – slowly, ever so slowly – towards a whirring saw. He remains in this utterly uncomfortable position for so long that his fainting seems entirely improbable. Still, in ‘The Usurer’s Son’ (1913), the Danish title of which translates directly as ‘Under the Teeth of the Saw Blade’, we get one of the first film scenes in film history where a machine slowly takes a defenceless victim closer and closer to certain death in a grinder, ship’s screw or, in this case, a timber saw. Just the ticket to get the audience perched on the edge of their seats – the sight of other people’s monstrous fates and inescapable doom quite simply makes for excellent viewing.

| The Usurer’s Son (1913) |

| Clip 1 |

It is hardly one of humanity’s most endearing traits, but who wouldn’t like to watch a man being thrown into the Copenhagen harbour from the raised bucket of a huge excavator? (‘The Modern Girl’, Clip 1) or being dragged after a speedboat dashing across the water in the self-same place? (‘The Modern Girl’, Clip 2).

| The Modern Girl (1912) | |

| Clip 1 | Clip 2 |

Or how about watching Carl Alstrup, off his head on cocaine, throwing himself from the wooden tower in the Copenhagen Zoo with an umbrella as a parachute, ending up one and a half metres into the ground, from where he cheekily courts a beautiful maiden passing by with the words: ‘As you see, Miss, I’ve been brought low with yearning for you’ – in The Cocaine Rush (1925) (Clip 1). Or what about The Girl from Whitley (1916) escaping from pirates? (Clip 2).

| The Cocaine Rush (1925) | The Girl from Whitley (1916) |

| Clip 1 | Clip 2 |

First in a dangerously flimsy cable car, then crawling high above an abyss with bare hands catching at the stretched steel wire of the cable car, and finally sliding on her bottom down the steep slopes at the cliffs of Møn. After all, she put her life and derriere on the line for our sake – for our entertainment. As did all the other stuntmen, stunt women and actors back in the first decades of filmmaking. So really, we owe them to watch!

Notes

1. Jan Nielsen: A/S Filmfabriken Danmark – SRH / Filmfabriken Danmarks historie og produktion. Side 243-244. Multivers 2003.

2. Jan Nielsen: Citat fra Politiken 28.03.1912. A/S Filmfabriken Danmark – SRH / Filmfabriken Danmarks historie og produktion. Side 245. Multivers 2003.

3. Jan Nielsen: Citat fra Ekstrabladet 11.09.1914. A/S Filmfabriken Danmark – SRH / Filmfabriken Danmarks historie og produktion. Side 553. Multivers 2003.

More about silent stunts

Lars-Martin Sørensen, Head of the DFI Research Unit, discusses the so-called 'sensation films', while stunt woman Anne Rasmussen provides insights into the daring stunts through a modern lens.